A recent Sino-Indian agreement to reopen the historic trade route of Lipulekh Pass in far-western Nepal has reignited a long-simmering border dispute between Nepal and India, exposing the fragile geopolitics of the Himalayas and the challenges of a multipolar world.

The recent visit of China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi to India yielded a seemingly pragmatic outcome: an agreement to reopen three Himalayan border passes—Nathu La, Shipki La, and Lipulekh—for cross-border trade. While the move aims to ease tensions and boost commerce between the two Asian giants, it has sparked a diplomatic firestorm. Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) has published a statement making it clear that the Constitution of Nepal includes the official map of the country, which unequivocally marks Limpiyadhura, Lipulekh, and Kalapani east of the Mahakali River as integral parts of Nepali territory.

The ministry has also urged the Government of India to refrain from carrying out any activities, such as road construction/expansion or border trade, in this area. It has asserted that “friendly nations, including China, have been informed that this territory belongs to Nepal.”

India’s rebuttal was swift. Its Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal called Nepal’s claims “not tenable, based on historical facts or evidence,” and “unilateral.” New Delhi maintains that trade via Lipulekh has been a consistent practice since 1954 and that it remains committed to resolving the boundary issue through diplomatic dialogue. This firm, uncompromising stance from India leaves little immediate room for negotiation.

The Lipulekh frontier dispute is not just a modern border quarrel—it is a story that has unfolded over nearly two centuries, shaped by treaties, maps, and shifting geopolitics. At the heart of the disagreement lies a simple but crucial question: where does the Kali River begin? Among an overwhelming wealth of content, the essays contained in Sam Cowan’s book “Maharajas, Emperors, Viceroys, Borders: Nepal’s Relations North and South”, the long essay “Territoriality amidst Covid-19: A primer to the Lipu Lek conflict between India and Nepal” and Ratan Bhandari’s book “Atikramanko Chapetama Limpiyadhura Lipulek” provide profound insights into this senstive topic.

The Lipulekh frontier dispute is not just a modern border quarrel—it is a story that has unfolded over nearly two centuries, shaped by treaties, maps, and shifting geopolitics.

The debate can be traced back to 1816, when the Treaty of Sugauli ended the Anglo-Nepal War. The treaty fixed Nepal’s western boundary at the Kali River, declaring all lands to its east Nepali territory. That sounds straightforward—until one asks: which stream is the “real” Kali?

Early British maps appeared to leave little doubt. An 1827 survey, for example, showed the river flowing northwest from Limpiyadhura. If that alignment were followed, villages such as Gunji, Navi, and Kuti—where Nepal once conducted censuses and even elections—would clearly fall within Nepal.

But by the 1860s, the maps had changed. The British, keenly aware of the value of the Lipulekh pass as a trade and pilgrimage route to Tibet, began marking a smaller tributary, the Lipu Khola, as the Kali’s headwaters. This cartographic adjustment quietly shifted the boundary eastward, placing the Limpiyadhura area under British India. Nepal’s Rana rulers, heavily reliant on British support, could do little to challenge the change.

The story did not end there. In 1950, with China asserting control in Tibet, India set up military posts along Nepal’s northern rim. Most were removed in 1969, but one outpost at Kalapani remained. To Nepal, the site lies on the eastern bank of the river and therefore on its side of the frontier. To India, relying on the altered maps, it is Indian soil. That lingering presence has since become one of Kathmandu’s most persistent grievances.

In recent years, academic research and historical investigations have breathed new life into Nepal’s claim. By revisiting the early maps and the language of the Sugauli Treaty, scholars argue that the larger Limpiyadhura region—long overlooked—rightfully belongs to Nepal. The Mahakali Treaty signed between Nepal and India on 12 February 1996, also clearly mentions that very river as the boundary. The same river that flows from Limpiyadhura past Kuti is identified upstream as Kuti Yangdi. Scholars maiantain that India has consistently perpetrated excesses upon Nepal by disregarding the very evidence and maps that it itself has long acknowledged and cited. The debate has since moved beyond cartography; it has become a question of national pride and sovereignty.

Ratan Bhandari asserts that Article 5 of the Sugauli Treaty states that the King of Nepal and his successors would abandon the territory west of the Mahakali River. This means Nepal only relinquished the land west of the Mahakali River. However, currently, India has occupied three villages—Kuti, Navi, and Gunja—east of the Mahakali River. From the maps prepared by the East India Company from 1816 to 1856, the river flowing from Limpiyadhura has been called the Kali River. The 1856 map was also agreed upon by Nepal. The maps issued based on bilateral agreements clearly state Limpiyadhura as the source of the Kali River. India claims that according to the 1954 agreement between India and China, a camp was established there.

Historical facts, evidence, correspondence, land records, and other documents confirm that Nepal’s western border is Limpiyadhura. Maps published by the British government from 1816 to 1856 serve as proof. The British Foreign Secretary’s letter to the Kumaon Commissioner instructed, “Since Kuti, Navi, and Gunji are Nepalese territories, surrender those lands to Bam Shah.”

After the agreement between China and India on 15 May 2015, to make Lipulekh a trade route, there was strong criticism in Nepal. Historically, there seems to have been an agreement between India and China in 1954 regarding Lipulekh, at a time when Nepal had not yet established diplomatic relations with China. India uses this as a basis to claim that Nepal did not object to the agreement, which is a flawed argument.

India also claims that according to that agreement, transportation and movement were allowed until 1962. After the 1962 war, that process was disrupted. During Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to China in 1984, there was an attempt to open the route. In 1999, Indian Foreign Minister Jaswant Singh visited China, and at that time a reporter from Amar Ujala wrote that another agreement was made about Lipulekh. This report caused a huge uproar in Nepal.

At a programme in Kathmandu in September 1999, Chinese Ambassador Zeng Xuyong said that when Nepal and China signed a border agreement, the Lipulekh Pass was designated as the tri-junction between Nepal, India and China, according to which the Kalapani area belongs to Nepal. However, during the agreement, older facts and evidences that extended the Nepali border to Limpiyadhura, the origin of the Mahakali River, were largely ignored. He also said that there has been no agreement between India and China regarding Lipulekh. But if the problem between Nepal and India regarding Kalapani is to be resolved, discussions can be held to make Limpiyadhura a tri-junction point, he had asserted.

This statement by the ambassador was the first time China spoke on behalf of Kalapani and Limpiyadhura’s rights. In 2005, during Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao’s visit to India, an agreement was made to make Lipulekh a trade route. In 2007, the Indian Parliament discussed Lipulekh. The Speaker clarified that there was an agreement between India and China regarding Lipulekh. Another agreement was made regarding Lipulekh during Xi Jinping’s visit to India in 2013, but the issue was not raised then. The issue flared up in Nepal only after another agreement during Modi’s visit to China in 2015.

The dispute resurfaced in 2019 after India published a new political map including that area after revoking the Article 370 of the Indian Constitution that gave special rights to Jammu and Kahsmir. Nepal government had registered its objection and sent a diplomatic note at that time. Subsequently on 8 May 2020 India’s Defence Minister Rajnath Singh, accompanied by high-ranking army officials, inaugurated an 80-kilometre road from Dharchula to Lipulekh, built in the encroached-upon area of Nepali territory. Stating that India’s move was unacceptable to it, the Government of Nepal delivered a diplomatic note to the Government of India through the Indian Ambassador Vinay Mohan Kwatra.

Nepal’s claim gained modern constitutional weight in 2020 when it officially amended its constitution to include a new political map incorporating Limpiyadhura, Lipulekh, and Kalapani within its sovereign territory. India dismissed this move as “artificial and unilateral,” further deepening the rift.

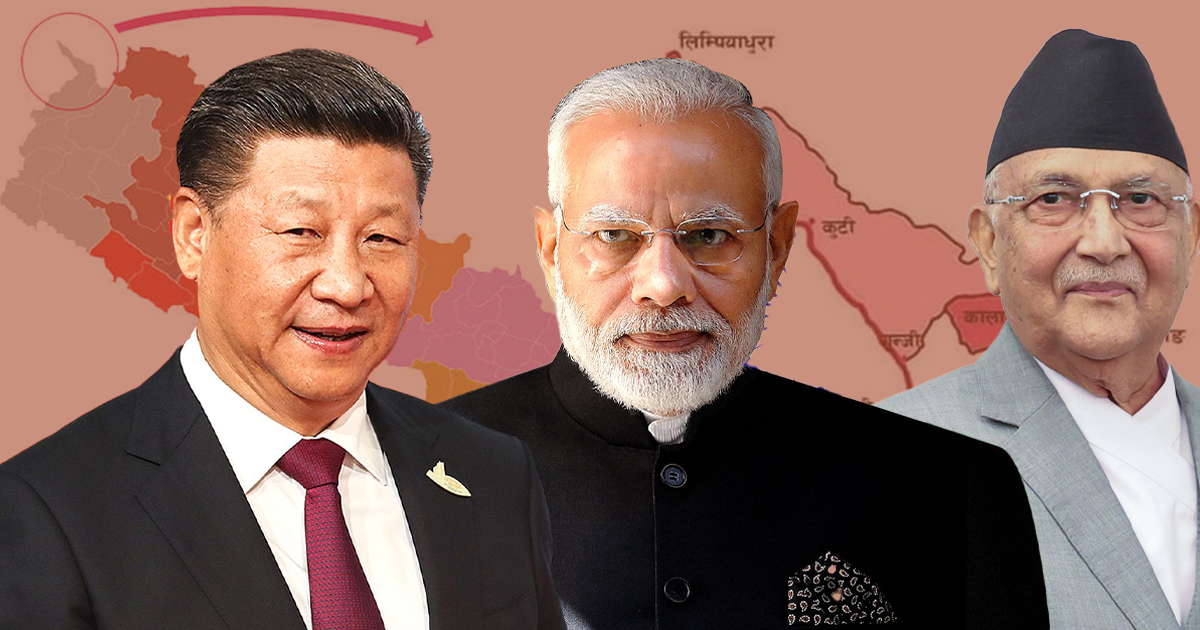

The situation presents a classic geopolitical triangle with each player adhering to a distinct narrative.

Nepal stands on a platform of national sovereignty, historical maps, and constitutional mandate. Its strategy combines diplomatic protests with a quest for international recognition of its claims, all while navigating its precarious position between two powerful neighbours.

India bases its position on the continuity of administrative control since the British era and established practice. It views the issue as a bilateral matter with Nepal to be resolved through quiet diplomacy, not under the spectre of third-party involvement or public pressure.

China is primarily driven by pragmatic economic and strategic interests. Its agreement with India on using Lipulekh is a function of trade convenience, not an endorsement of India’s territorial claims. Beijing appears content to pursue its commercial corridors while avoiding direct entanglement in the sovereignty debate between Kathmandu and New Delhi.

Nepal stands on a platform of national sovereignty, historical maps, and constitutional mandate. Its strategy combines diplomatic protests with a quest for international recognition of its claims, all while navigating its precarious position between two powerful neighbours.

Nonetheless, the lack of a forceful assertion of the sovereignty over Kalapani-Lipulekh-Limpiyadhura territory highlights a fundamental weakness of the Nepali state. This failure stems from an inability to advance diplomatic talks and negotiations with India and China based on its unilaterally issued new map and constitutional amendment, and a failure to register the border dispute according to international law. Consequently, the two neighbouring giants have moved forward, disregarding Nepal.

The timing of India’s public announcement of this agreement is particularly striking, coming just as the Prime Minister, who championed the map-printing diplomacy, was on the verge of an official visit to India. Serious questions are now being raised. Why has the report by a nine-member team of experts under the coordination of Bishnuraj Uprety, the then executive chairman of the Policy Research Institute, to collect evidence, historical facts, and documents to support Nepal’s claim to Kalapani, Lipulekh and Limpiyadhura not been made public to this day? If the facts and evidence in that report were indeed credible, why were they not presented through diplomatic dialogue? Why were no preparations made to take the border dispute to a legal process under international law? Why was Kathmandu unable to negotiate this matter with India and China?

The Government of Nepal must take a firm stance to either register this dispute at The Permanent Court of Arbitration in line with the international law, or initiate trilateral high-level talks to resolve the issue amicably. The statements issued by both Nepal and India have provided space for further dialogues to settle the boundary dispute. Since India and China have agreed to settle their border (Line of Actual Control), it is an opportune time for Nepal to chip in to resolve the niggling issue for good.

Can Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli raise this issue during his imminent visit to India? That is a million-dollar question because Oli incites populist sentiments while in Nepal but keeps mum in the presence of his Indian counterpart. He cannot play this game forever.

Most critically, Kathmandu must pursue relentless and creative diplomacy. This means not just issuing notes of protest but actively proposing solutions, such as the formation of a joint boundary commission with India dedicated to technical and historical investigation. Enhancing cultural and religious ties to the area, documented through centuries of pilgrimage to Kailash Mansarovar, could also strengthen its soft power claim.

For all three nations, the Lipulekh dispute is a stark reminder that in an interconnected world, no action is truly bilateral. The Himalayas are not just a geological feature but a political ecosystem where the moves of one player send tremors through the others. A sustainable solution will require not just historical righteousness or administrative stubbornness, but a delicate balance of national interest, regional cooperation, and diplomatic wisdom.

Comment Here