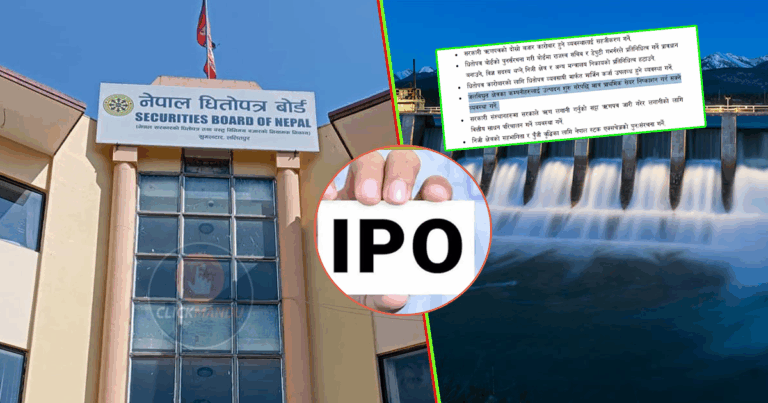

Kathmandu: The government-appointed High-Level Economic Reform Recommendation Commission has reignited debate over hydropower companies’ initial public offerings (IPOs) after recommending that such firms be allowed to issue shares only after they begin electricity production.

Chaired by former finance secretary Rameshwor Khanal, the commission argued that investors face uncertainty under the Build-Operate-Own-Transfer (BOOT) model, where shares may lose value once production licenses expire. The commission’s report suggested introducing safeguards by restricting IPO issuance until projects commence operations.

The Economic Reform Implementation Plan 2082 (2025/26), created to carry out the commission’s proposals, has formally adopted this provision. It explicitly states that “hydropower companies will be permitted to issue IPOs only after starting production,” and tasks the Finance Ministry and the Ministry of Energy, Water Resources and Irrigation with implementing the rule within two years.

Following this, the Securities Board of Nepal (SEBON) incorporated the provision into its policy and program for fiscal year 2082/83 (2025/26), stating that IPOs for hydropower companies would be conditional on production commencement. The Cabinet-endorsed implementation plan also reflects this mandate.

Hydropower developers have strongly opposed the recommendation, arguing that IPOs are essential to raise capital during the construction phase rather than after projects start generating electricity. They claim the commission misunderstood the sector’s needs when drafting its proposals.

Investors in the sector have asked: “If IPOs are only allowed after generation begins, why would we need capital at that stage?” Hydropower companies stress that funding is required to build projects, not after revenue streams are already established.

In response, SEBON has already initiated preliminary discussions to amend securities registration and issuance regulations. The board is also debating how to align its rules with the commission’s recommendations, while a new hydropower bill is simultaneously under preparation.

Independent Power Producers’ Association of Nepal (IPPAN) president Ganesh Karki said the policy risks discouraging investment. “Developers need money to build plants, not afterward,” he said, adding that if IPOs are restricted until post-production, then companies should at least be allowed to issue them at a premium.

Karki further criticized the contradiction of simultaneously requiring companies to offer at least 10 percent of shares to the public by law while discouraging IPO issuance. He argued that existing policy is broadly functional and should instead be refined through stronger regulation rather than restrictive changes.

Senior IPPAN vice president Mohan Kumar Dangi went further, suggesting that instead of delaying IPOs, the law should be amended to prohibit hydropower IPOs altogether. “If companies are not allowed to issue shares at all, it will remove uncertainty once and for all,” he said.

Under the Securities Registration and Issuance Regulation 2016, companies can issue IPOs ranging from 10 percent to 49 percent of paid-up capital, unless regulators specify otherwise. For hydropower companies, this framework has long allowed public participation.

Dangi argued that the system fuels market distortions, with shares issued at Rs 100 being traded by retail investors at Rs 1,000–1,200. “Companies cannot sell at fair value or participate in the secondary market. Instead of perpetuating such practices, it would be better to eliminate IPOs for the sector altogether,” he said.

SEBON is now under pressure to clarify its position. While the government has committed to implementing the commission’s recommendations, officials acknowledge the proposal has sparked controversy. “The IPO issue is the most debated part of the amendment process. Given the criticism, it will not be easy to enforce,” one SEBON official noted, adding that discussions remain ongoing.

The commission also flagged broader investor risks. It warned that many investors are unaware of the direct impact of the BOOT model on share prices, particularly after the 50-year production license period expires. Without clear provisions, uncertainty over the fate of shares could pose risks greater than Nepal’s troubled savings and credit cooperatives sector.

The report further cautioned that some companies with negative net worth are still trading at high valuations in the secondary market, raising the likelihood of investor losses in the future.

As SEBON undertakes internal regulatory revisions, it is closely reviewing the commission’s concerns, including potential capital entrapment in BOOT projects and investor protection once production licenses expire.

Comment Here