Kathmandu: With the fall in deposit interest rates, savers have stopped keeping money in fixed deposits. Banks are now offering barely above 5 percent interest on long-term deposits of 5 to 10 years, while the rate for deposits of two years or less has dropped below 4 percent.

As a result, the general public has stopped placing or renewing fixed deposits, leading to a continuous decline in the share of fixed deposits in banks’ total deposits.

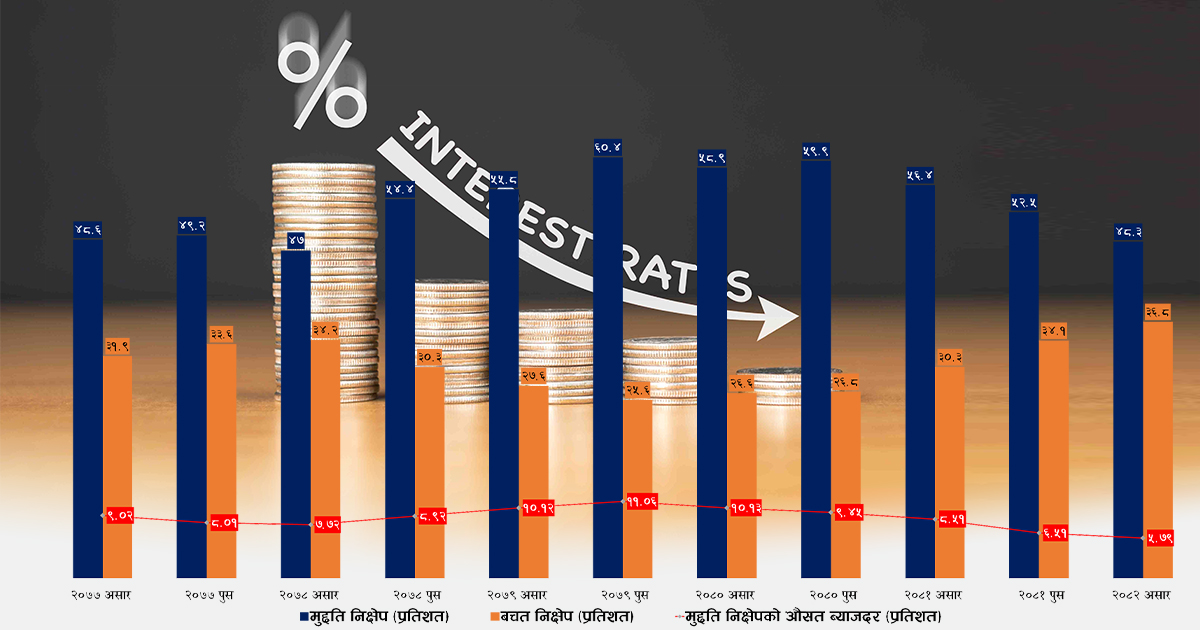

At one time, fixed deposits made up more than 60 percent of total deposits. Now, that share has dropped to 48 percent, according to data from Nepal Rastra Bank (NRB).

Over the past two and a half years, the decrease in fixed deposit rates has been accompanied by a decline in their share of total deposits. Since banks invest long-term loans in hydropower, hotel, and cement projects but rely mainly on short-term deposits, this mismatch has created challenges in managing financial resources.

Economist Dr Prakash Kumar Shrestha, former Executive Director at NRB, warns that investing long-term while mobilizing short-term funds can create serious risk due to resource mismatch.

Two and a half years ago, deposits with maturities of over one year made up 23.71 percent of total deposits in Nepali currency. By the end of Ashar 2082 (mid-July 2025), that share had dropped to 21.27 percent.

In Poush 2079, deposits of two years or longer made up 12.91 percent of total domestic currency deposits, earning an average interest rate of 10.80 percent. Deposits of one to two years accounted for 10.54 percent, with an average rate of 10.86 percent. The largest portion — 20.61 percent — consisted of deposits with maturities between six months and one year, earning an average of 11.06 percent. The highest average rate, 11.43 percent, was for deposits of three to six months, which made up 14.70 percent of total deposits.

By Ashar 2082, the share of fixed deposits in total deposits had declined. Even though long-term deposits generally offered higher rates, deposits of two years or longer had dropped to 12.26 percent of total domestic currency deposits, with an average rate of 9.43 percent. Deposits of one to two years made up 9.01 percent, with the average rate plunging to just 5.22 percent.

Deposits with maturities between six months and one year now make up 17.51 percent of total deposits. The average interest rate for such deposits dropped from 11.06 percent in Poush 2079 to 4.36 percent in Ashar 2082, according to NRB data.

Similarly, the average interest rate for three- to six-month deposits — which previously stood at 11.43 percent in Poush 2079 — has dropped to 4.14 percent. Their share in total deposits has also fallen from 14.70 percent to 8.73 percent.

In Poush 2079, savings deposits accounted for only 26.5 percent of total deposits; now that share has risen to 36.8 percent. The majority of fixed deposits are for less than one year, and short-term savings are also rising. This means roughly three-fourths of bank resources are now short-term.

Meanwhile, around 40 percent of total loans are term loans, and some banks have even introduced 30-year home loan plans. This indicates that banks are using mostly short-term funds for long-term investments. Some bankers say that, with excess liquidity, banks do not even need to accept fixed deposits, and many institutions are no longer participating in fixed deposit tenders.

When loanable funds are scarce, banks tend to raise interest rates sharply; when liquidity is high, they cut them heavily. The average interest rate on deposits longer than two years remains above 9 percent because many older deposits taken at 12 percent interest are still active. However, high-interest deposits of one to two years have already matured. Those who previously locked in deposits at 10–12 percent are now being offered just 4–5 percent upon renewal — leading many to prefer savings accounts instead of fixed deposits.

Banks say that currently only institutional depositors, who are required to maintain term deposits, are renewing or opening new fixed deposit accounts. Individual depositors who previously used to invest in fixed deposits have largely stopped doing so.

“Renewal of individual fixed deposits is almost negligible. When savings accounts earn around 3 percent and fixed deposits of six months to two years earn only 4–5 percent, people see little difference between the two,” one banker told Clickmandu.

Data also shows a clear trend — when fixed deposit rates rise, savings decline and term deposits increase; when rates fall, fixed deposits shrink and savings grow. Nepal’s banking sector has shown a pattern of sharp swings: during liquidity shortages, interest rates soar; when liquidity improves, they drop quickly. In Poush 2079, the highest fixed deposit rate (11.43 percent) was for 3–6 month deposits, while average savings interest was just 7.44 percent. Now, the same deposits offer 4.14 percent on average, and savings yield about 3.37 percent. Over two and a half years, banks have reduced the interest rate on 3–6 month deposits by 7.29 percentage points, and on six-month to one-year deposits (the largest segment), the rate has fallen from 11.06 percent to 4.36 percent, a drop of 6.70 percentage points.

This shows that banks have been causing sharp short-term fluctuations in deposit interest rates.

In Ashar 2077, the average fixed deposit rate was 9.02 percent, with fixed deposits making up 48.6 percent of total deposits. During the post-COVID period, as rates declined, their share fell to 47 percent by Ashar 2078, when the average fixed deposit rate was 7.72 percent. Later, as rates rose again, the share of fixed deposits also increased.

By Poush 2079, when the average fixed deposit rate peaked at 11.06 percent, the share of fixed deposits reached 60.4 percent — the highest level. Since then, as interest rates have fallen, the share has also dropped, reaching 48.3 percent by Ashar 2082, according to NRB data.

Economist Dr Prakash Kumar Shrestha, also a former NRB Executive Director, warns that when banks collect short-term deposits but make long-term investments, it creates a maturity mismatch risk.

“Even if the long-term investments and funding sources don’t perfectly match, they should at least be close. But that isn’t happening,” said Shrestha. “This mismatch is causing large swings in interest rates. Banks have cut not only short-term but also long-term deposit rates due to excess liquidity. Yet, lower rates make long-term deposits unattractive.”

He added that if banks were to offer roughly similar long-term deposit rates as they do now — slightly below or above 9 percent — then even if rates rise later, the mismatch problem would cause less volatility. However, because banks focus only on short-term conditions and lack long-term planning, both interest rate volatility and funding mismatches persist.

With deposit rates now at historic lows, investors are showing growing interest in bonds. Some banks have issued bonds as required by NRB’s policy, but Nepal’s corporate bond market is still underdeveloped and not widely used for fundraising.

Due to the lack of alternative investment instruments, the sharp fall in deposit rates may gradually push savers toward real estate and the stock market, while also boosting household consumption, according to Shrestha. He cautioned that while banks currently face no liquidity shortage thanks to strong remittance inflows and reduced imports, if banks fail to utilize this liquidity effectively, even a small decline in remittances could revive the liquidity crisis of the past.

Comment Here