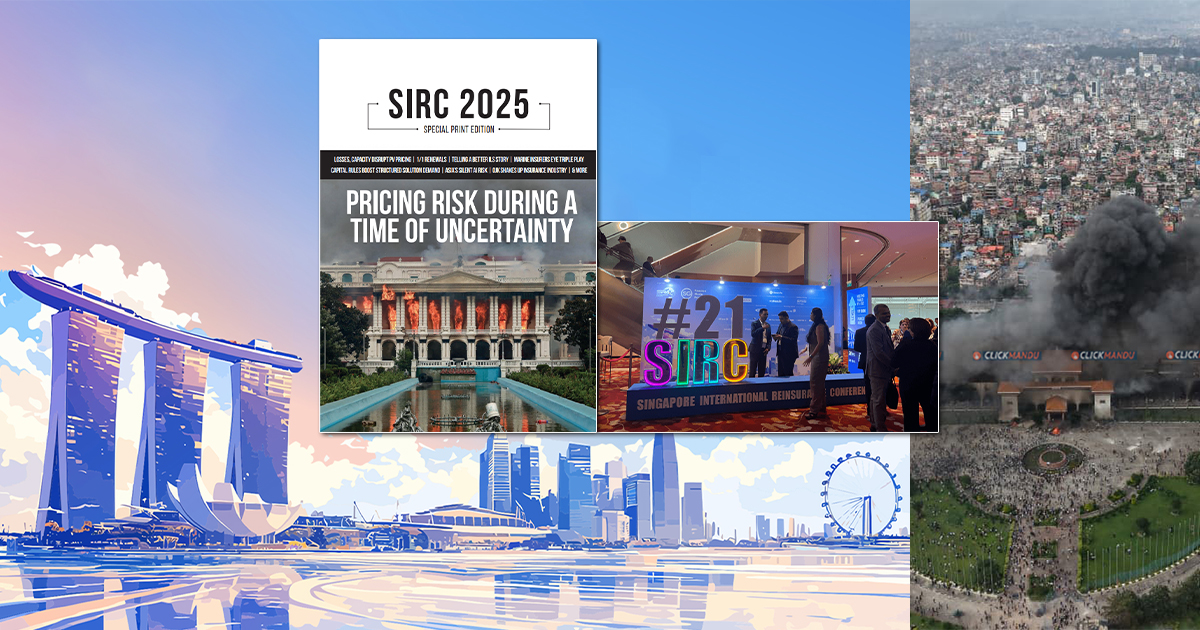

Kathmandu: When the world’s reinsurance giants gathered last month at the Singapore International Reinsurance Conference (SIRC), the most talked-about publication handed out at the venue carried a dramatic cover: Nepal’s iconic Singha Durbar parliament building engulfed in flames.

The photo, taken during the violent “Gen-Z protests” on 8–9 September 2025, accompanied the headline of the special SIRC 2025 print edition of (Re)in Asia, the region’s leading insurance intelligence platform.

The opening line of the cover story was blunt:

“Something unusual is happening in the world of political-violence insurance. Just when losses are skyrocketing, the global reinsurance market’s capacity to absorb those losses is also rising dramatically.”

In plain language: the price of insuring against riots, civil unrest and political violence is too low for the risks that now exist – and the market knows it.

By choosing a blazing Singha Durbar as its cover image, (Re)in Asia sent a clear message to hundreds of underwriters and brokers from Munich Re, Swiss Re, Hannover Re and Lloyd’s syndicates: political-risk coverage in the Asia-Pacific region has been dangerously under-priced, and Nepal’s 2025 protests are Exhibit A.

The embarrassment for Nepal was instant and international. Senior delegates at the conference openly discussed the photograph, with many asking the same uncomfortable question now echoing through reinsurance trading floors worldwide: “Is the premium we are charging for political violence and riot cover anywhere near adequate?”

How insurance pricing actually works

Insurance and reinsurance prices (premiums) are supposed to reflect risk. When claims rise, capacity should tighten and prices should go up. That is basic actuarial science. Yet for years, even as riots and civil commotion events exploded across the Asia-Pacific region, premiums for political-violence coverage stayed remarkably flat.

The reason? An flood of new capital. Fresh reinsurance startups in London, Singapore and Dubai, hungry for market share, have been writing coverage aggressively and often at rates that more conservative players consider unsustainable. Intense competition has kept prices down even as losses have soared.

But the data is now impossible to ignore:

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) shows the Asia-Pacific region has suffered more protests and riots in the past four years than any other part of the world – from 16,000 events in 2016 to over 51,000 in 2023.

Swiss Re’s chief economist Victor Kuk says individual riot events that once caused under US$ 1 billion in damage now routinely exceed US$ 3–4 billion.

Recent benchmark losses include:

– New Caledonia 2024 riots: ~US$ 1 billion

– France 2023 riots: €730 million

– U.S. 2020 unrest: >US$ 2 billion

– Chile 2019 protests: US$ 3–4 billion

– Nepal 2025 Gen-Z protests: estimated insured losses >US$ 150 million and counting

Even though these figures are staggering, political-violence reinsurance rates have barely moved – until now.

Industry insiders say Nepal’s burning parliament on the SIRC cover has become a turning point. Deepam Pandit, Asia-Pacific head of war and terrorism at Liberty Specialty Markets, told delegates: “Political violence is increasingly breaking out in places we never expected.” Steve Heaton, regional terrorism manager at Beazley, predicts the current wave of tension will continue for another 12–18 months.

The hidden cost of “cheap” coverage

When risks are systematically under-priced, someone eventually pays. In the short term, new entrants gain market share. In the long term, the entire industry faces the threat of severe under-reserving and possible insolvencies when the next big wave of claims hits.

(Re)in Asia warns that unless the market collectively starts charging technically adequate rates, the current “soft pricing” cycle will end in tears. Yet as long as billions in fresh capital keep flowing in, underwriters feel pressure to keep rates low to protect their portfolios.

What this means for Nepal and the region

Nepali insurance expert Rabindra Ghimire notes that global reinsurers have already started quietly adjusting prices upward, even if the increases are small and gradual. “When claims and instability rise, reinsurers have no choice but to recalibrate pricing over time,” he says. “Policies need to properly address riots, strikes and civil commotion that were previously considered remote risks.”

For ordinary Nepali businesses and households, the consequence is straightforward: fire, property and business-interruption premiums – already rising because of natural-catastrophe risks – will face additional upward pressure from the political-violence component that global reinsurers now see as severely under-priced.

A single photograph of a burning parliament has done what years of lobbying could not: it has put Nepal’s 2025 protests on the radar of every major reinsurance CEO on the planet, and the bill for that global attention is about to arrive in the form of higher insurance costs for everyone.

Comment Here