Kathmandu: Every year, as festivals like Tihar approach, millions of rupees leave Nepal because the decorative lights that brighten homes, streets, and markets are not produced domestically.

In Nepal, there is a tradition of lighting decorative bulbs during festivals such as Tihar, Chhath, Christmas Day, and weddings. The decorative lights used in these celebrations are entirely imported.

According to Resham Devkota, President of the Nepal Electric Business Federation, Nepal imports millions of rupees worth of such lights every year because they are not produced locally. If these lights were manufactured in Nepal, at least 50,000 Nepalis could find employment opportunities.

“If we could produce these decorative lights within Nepal, not only would we save our currency from going abroad, but we could also create employment for at least 50,000 Nepalis,” Devkota said. “However, due to the lack of advanced technology and investment, we are compelled to depend on imports every year.”

Devkota said that since there is a large global market for decorative lights, Nepali industrialists could make the country self-reliant by investing in this sector and even earn significant foreign exchange through exports.

Within just the first two months of the current fiscal year, decorative lights worth Rs 260 million — totaling 2,608,792 pieces of different designs and colors — were imported into Nepal.

According to Devkota, since early Asar this year, Nepal’s two main northern trade routes — Rasuwagadhi and Tatopani — have remained completely blocked, leaving a large quantity of prepared lights stuck in China.

“If the routes had not been blocked, lights worth at least Rs 400 million would have arrived,” Devkota said. “Even now, many Nepali traders have their goods stranded in China. Although the Korala route opened in Ashoj, only a small quantity has come through there. Some traders have transported goods through the Kolkata port by sea, despite higher shipping costs.”

The decorative lights that arrived via Kolkata Port and reached Birgunj are now being distributed across the market, he added. Although some orders could not reach Nepal on time due to route disruptions, Devkota assured that there would be no shortage of lights in the market this year.

“There was a large stock of lights left over from last year, and those are also being sold this year. So even though we didn’t receive all the new orders from China, there will be no shortage in the domestic market,” Devkota said.

According to data from the Department of Customs, Nepal imported 8,068,000 pieces of decorative lights worth Rs 1.43 billion in the last fiscal year 2025/25.

Nearly 80 to 85 percent of the total annual sales of these lights occur during Tihar. The remaining demand comes from Chhath, Christmas, New Year, national festivals, hotels, restaurants, and special occasions like weddings and Bratabandha ceremonies, the Federation said.

In the past seven years, the highest import was recorded in fiscal year 2023/24, with 9,954,549 pieces of lights worth Rs 1.78 billion brought into Nepal. The lowest import was in 2022/23, with 260,578 pieces worth Rs 80 million.

In total, decorative lights worth Rs 6.4 billion have been imported into Nepal over the past seven years.

According to the Federation, the decorative lights used during Tihar are imported mainly from neighboring countries like China, India, Bahrain, Australia, and Hong Kong.

More than 80 percent of total imports come from China, followed by India. Imports from other countries are minimal.

According to Hindu tradition, the festival of lights, Laxmi Puja, will be celebrated across the country next Monday. On this day, the goddess of wealth, Laxmi, is worshipped with great devotion.

This festival is celebrated in the belief that Goddess Laxmi will reside in homes and shops, ensuring prosperity throughout the year. The festival feels incomplete without illumination — light and Tihar are inseparable.

Rising consumption from cities to villages

Recently, the consumption of decorative lights has increased from rural to urban areas, which has also pushed up imports. Ten years ago, these lights were not accessible to everyone.

There were two main reasons for this: first, there was no reliable electricity supply in rural areas, and second, the lights were too expensive, affordable only to the wealthy. At that time, lighting decorative bulbs at homes, corporate houses, industries, and businesses was considered a status symbol for the rich.

In rural areas, people used to celebrate Tihar by lighting small lamps (tuki) using kerosene or diesel in front of their homes, on rooftops, and on walls. Mustard oil lamps were used for worshiping gods and goddesses.

In recent years, however, due to the availability of reliable electricity and the end of load-shedding, along with the impact of remittance income, the use of decorative electric lights has spread rapidly to rural areas.

“The growth of the decorative light business can be credited first to an end to load-shedding and second to remittance income,” Devkota explained. “Because of remittances, people in rural areas now also use decorative lights during Tihar and Chhath. The tradition of celebrating Tihar with kerosene lamps has almost disappeared.”

In areas still without electricity, people continue to use kerosene, mustard oil, or diesel lamps, as well as candles, to illuminate their homes and courtyards.

According to Devkota, people who build new houses tend to spend heavily on decorative lighting for the first two to three years. Since decorating new houses with lights during Tihar has become a trend in both urban and rural areas, consumption and imports have risen accordingly.

“However, in recent years, consumption has started to decline,” he said. “The slowdown in the real estate market and a large number of young people migrating abroad have also affected demand. Buying and setting up decorative lights is mostly done by young men, and their migration has directly impacted this business.”

Slow business and market prices

The Federation expects that this year too, the decorative light business will not perform well. After suffering from economic slowdown and weak purchasing power last year, traders now face additional uncertainty due to the unstable political situation.

“Not even 50 percent of the goods we ordered have arrived on time,” Devkota said. “The market has shrunk due to political instability. Normally, decorative lights start selling about a week before Tihar, but this year, because of import delays, we’re only now sending last year’s stock to districts.”

According to the Federation, the current market price for standard string lights ranges between Rs 150, Rs 200 and Rs 500.

Meanwhile, waterfall lights are priced between Rs 1,500 and Rs 4,000, suitable for decorating four- or five-storey houses.

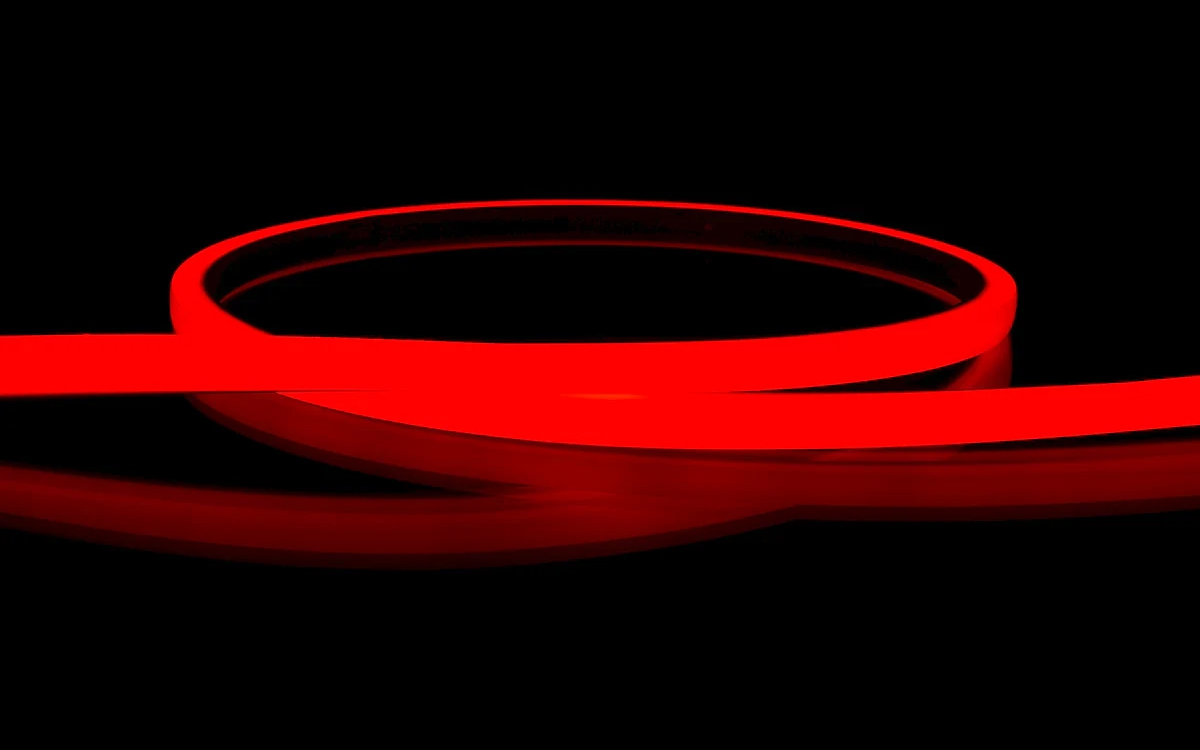

Rope lights — LED lights encased in white plastic tubes — cost between Rs 90 and Rs 250 per meter, depending on tube thickness, LED size, and design. These are waterproof, making them more durable and expensive.

According to Devkota, lower-income households mostly use string and curtain lights, while wealthier families prefer rope lights. There is also high demand for strip lights, pipe lights, net curtains, illuminated idols of Goddess Laxmi and Lord Ganesh, and LED photos.

“The front parts of houses are often fully decorated with curtain, string, and rope lights from top to bottom,” Devkota said.

Such lights are widely used in homes, shops, corporate buildings, hotels, restaurants, and streets, making them the top-selling products in the market.

String lights come in various designs, colors, thicknesses, and lengths, typically lasting two to three years.

A standard 10-meter string light with 100 LEDs is sold wholesale for Rs 150, while a 20-meter version with 200 LEDs costs around Rs 300.

These lights are mainly used to decorate houses, shops, corporate offices, and streets. A two-and-a-half-storey house requires about 10 meters of lights, while a three- to five-storey building needs 20 to 30 metres, according to the Federation.

Apart from these, rope lights are also among the best-selling products. Those willing to spend more generally prefer rope lights.

The Federation estimates that around 5,000 traders across Nepal are engaged in the decorative light business. In Kathmandu, the main trading areas include Bhotebahal, Koteshwor, Baneshwor, Mahabauddha, Asan and New Road.

Comment Here