Kathmandu: Prominent stock investor Dipendra Agrawal has been apprehended by the Central Investigation Bureau (CIB) of the Nepal Police on charges of orchestrating a sophisticated market manipulation scheme.

Authorities allege that Agrawal did not merely influence other investors through public commentary but actively engaged in fraudulent trading by utilizing 15 different accounts to artificially inflate stock prices. The CIB initiated the investigation following his arrest on Friday, accusing him of reaping illegal profits by disseminating deceptive information and conducting wash trades—a practice where shares are bought and sold without any change in actual ownership.

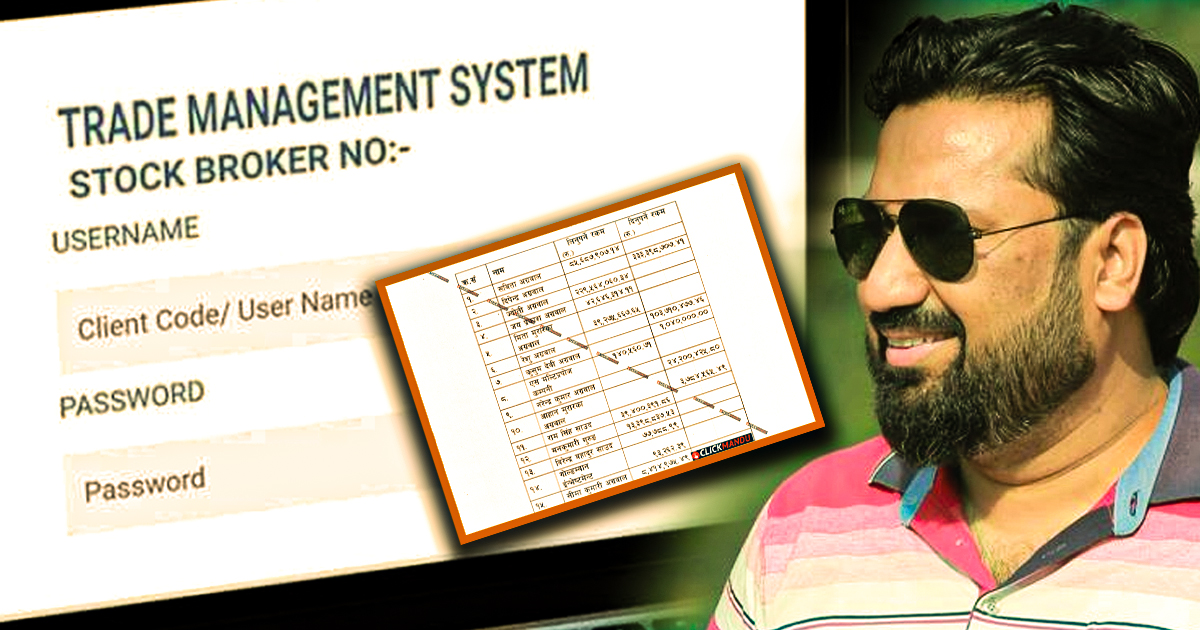

The investigation focuses on Agrawal’s exploitation of various Trading Management System (TMS) accounts to conduct circular transactions among family members and associated entities. By trading shares between these accounts, he allegedly created a false impression of market activity to drive up prices. Specifically, the CIB has targeted his activities involving Joshi Hydropower and Corporate Development Bank, asserting that he violated Section 97(c) of the Securities Act (2006) by publishing misleading statements and promises to deceive the investing public.

According to a preliminary report by the Securities Board of Nepal (SEBON), Agrawal utilized a network of 15 TMS accounts to execute these sham transactions. Ironically, his own legal disputes with brokerage firms helped expose the scale of his operations. In a complaint filed against Cipla Securities regarding outstanding payments, Agrawal listed ten different accounts—registered under the names of his family members and shell companies—with whom the brokerage supposedly had unresolved financial dealings. These names included his wife, parents, and other relatives, as well as entities like S Multipurpose Company.

The financial friction between Agrawal and Cipla Securities further revealed the complexity of his trading web. While Agrawal claimed he was owed over Rs 108 million (including interest) through ten accounts, the brokerage firm countered by asserting that Agrawal actually owed them Rs 7.4 million.

Cipla’s report to SEBON identified five additional accounts beyond the ten Agrawal had admitted to, totalling 15 users under his direct control. SEBON noted that the brokerage and Agrawal often settled accounts in bulk rather than on a per-transaction basis, a practice that suggests a violation of the Anti-Money Laundering Act by obscuring the true nature of the professional relationship and the identity of the beneficial owner.

Financial analysis of the bank accounts associated with these 15 TMS users showed frequent fund transfers intended to facilitate and adjust trading settlements between the individuals. SEBON’s report highlighted that Cipla Securities was aware of this arrangement but failed to properly verify the clients’ identities, making the firm a potential accomplice in the securities violation.

Surveillance data from the Nepal Stock Exchange (NEPSE) corroborated these findings, showing that shares were repeatedly cycled through the same group; for example, one relative would sell shares that Agrawal would buy, who would then sell them to another associate.

This pattern of circular trading was identified in the stocks of numerous listed companies, including Sindhu Bikash Bank, Corporate Development Bank, Green Development Bank, and several insurance and hydropower firms. SEBON emphasized that because the ultimate control of these shares remained within Agrawal’s circle, the transactions were “fictitious” under Section 94 of the Securities Act. Such activities are designed to create a misleading appearance of active trading or to maintain an artificial price for a security.

The investigation also uncovered a massive flow of funds involving dozens of checks. In one instance, Cipla Securities issued 38 checks totalling nearly Rs 380 million to Agrawal, which were then moved through his relatives’ accounts and cycled back to the brokerage. The repetitive and circular nature of these payments provided investigators with strong evidence that the various account holders were merely proxies for a single beneficiary.

Furthermore, other brokerages, including Shreekrishna Securities and Hatemalo Financial Services, were found to have neglected their “Know Your Customer” (KYC) obligations by failing to identify Agrawal as the final beneficial owner of these accounts.

One of the most striking examples of price rigging occurred in April 2025 with Corporate Development Bank. During the final 15 minutes of a trading session, an account under the name of Jyoti Agrawal sold 20,000 shares which were immediately purchased by Smart Doors Limited—a company directed by Dipendra Agrawal and owned by his family members.

This wash trade artificially spiked the bank’s closing price by more than 116 points. Investigators concluded that without this fraudulent transaction, the market price would have been significantly lower, proving a direct violation of Section 95 of the Securities Act regarding price manipulation.

Beyond technical trading violations, the report details how Agrawal used social media and video content to “pump” stocks. After accumulating shares through his various accounts, he would allegedly post claims about imminent price surges, upcoming rights shares, or “circuit” limits to entice unsuspecting retail investors to buy, allowing him to sell his positions at an inflated price.

The CIB maintains that these actions constitute the malicious publication of false or misleading statements as defined under Section 97 of the Act. If convicted, Agrawal faces significant fines, up to two years in prison, and the requirement to compensate any investors who suffered losses as a result of his market interference.

Comment Here